Dams: Architecture Beyond Monumentality

Sayano-Shushenskaya

In the southern expanse of Siberia, where the Yenisei River cuts deep through mountain ridges and taiga forests, rises a colossal curve of concrete: the Sayano-Shushenskaya Hydropower Station. The largest hydroelectric plant in Russia, and once the sixth-largest in the world, it is more than a feat of engineering. It is a monument it’s a symbolism and permanence, it anchors a vision of progress carved into landscape, cast in concrete, and soaked in political will.

Published in October 2025

Engineering the Territory, Architecture of Control

The dam is inseparable from the Soviet project of infrastructural conquest, the systematic reshaping of space, nature, and people in the name of energy and control. It was never only about electricity. It was about taking possession of territory through grids, flows, and systems, about embedding ideology into topography. The Sayano-Shushenskaya dam stands as a clear case of how infrastructure can become architecture and how architecture can serve as a tool of statecraft.

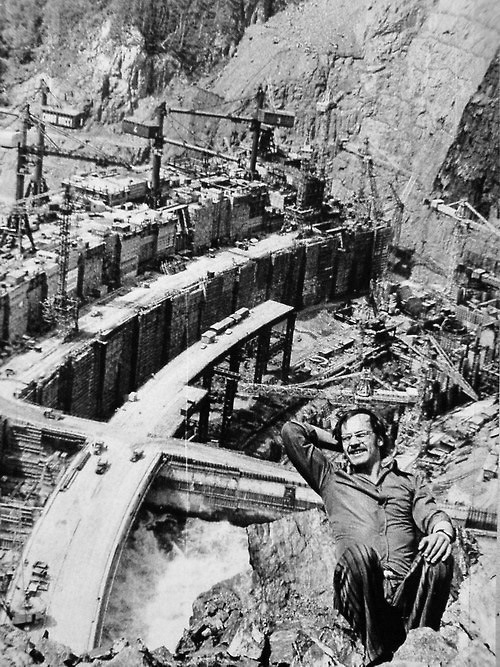

Construction began in 1968, during the final decades of Soviet industrialization. Siberia, once treated as distant and marginal, was reimagined as a strategic heartland rich in untapped resources. To realize this vision, large-scale hydraulic projects were launched, aiming to turn the river systems into engines of economic output. The Yenisei was one of the last major rivers to be dammed. The project’s ambition was not limited to technical parameters. It required coordination across ministries and institutions, and its realization was viewed as a matter of national priority. The dam was designed as a 242 meter high concrete arch-gravity structure, forming a reservoir over 621 square kilometers. It was intended to supply energy to heavy industries, transport infrastructure, and planned settlements across the region.

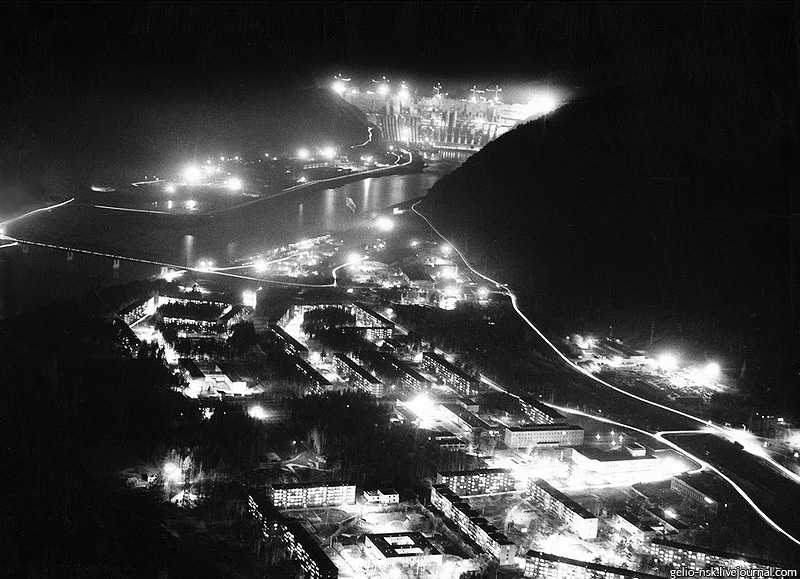

In practice, this meant redrawing the landscape. Villages were displaced, cemeteries submerged, agricultural zones erased. Entire communities were relocated, some by choice, many by directive. Official reports described this as voluntary participation in the national cause. Unofficially, stories circulated of disruption, refusal, and loss. The natural terrain was altered, but so too were the social and cultural geographies attached to it. The territory was no longer only inhabited it was administered.

New towns that appeared near the construction zone followed a uniform model. Their architecture reflected the dam’s own design logic: functional, severe, stripped of excess. These were not spaces of civic life, but of logistical efficiency built not to host society, but to sustain infrastructure.

The physical presence of the dam reflects its governing idea. Its shape massive and linear is not expressive, but imposed. Spanning between two cliff faces, it blocks the river’s motion and channels its energy downward, into the state’s productive system. There is no attempt at formal grace. Its message is force, not elegance.

Though it serves a practical function, the dam is also deeply symbolic. It rendered visible the ideological and technical priorities of its time. It was an assertion of control over nature, over production, over the future. For Soviet planners, it stood as evidence of an organized order, where power could be planned, scaled, and monitored. In this sense, the dam functioned not only as a power station, but as a spatial declaration. Yet this same imperative to demonstrate capability at all costs led to technical decisions that undermined the dam’s long-term integrity.

Construction Under Pressure

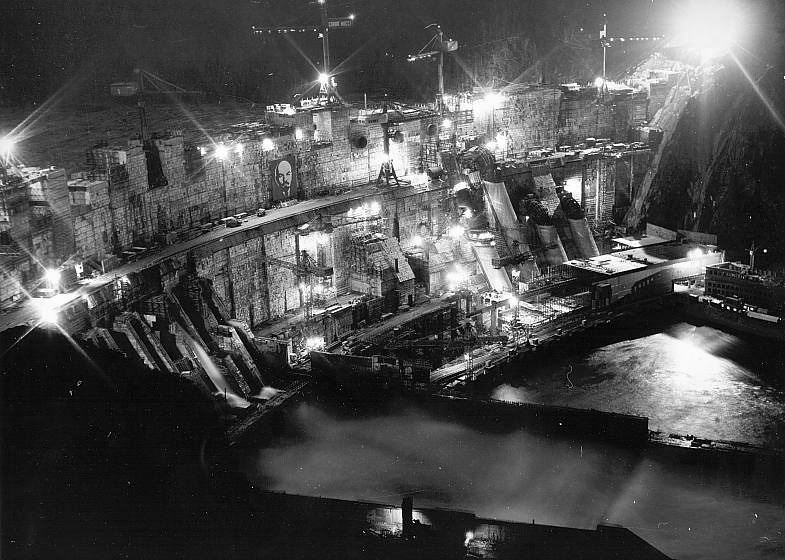

From the outset, the Sayano-Shushenskaya project was driven by political timelines as much as technical ones. Deadlines loomed, prestige was at stake, and central planners were under pressure to show visible progress. This urgency led to a series of engineering compromises that would haunt the dam for decades. Construction officially began in 1968, and by 1970 the first concrete was poured. The river was diverted in 1975. But crucial sections of the dam were not yet structurally complete. In December 1978, the first hydroelectric unit was brought online while the dam body was still incomplete. This meant hydrostatic pressure was applied to a weakened profile supported by only three of the four planned vertical concrete blocks (called “piers”). The fourth pier, essential for equal load distribution, had not yet been finalized. Experts later described this as a critical structural and political error. It was a decision made not for safety, but for optics. As hydroengineer E.A. Dolginin later wrote, “This voluntarist decision served only favorable reporting. The result: a sick dam.” Within months, the risks became evident. In May 1979, a flood event caused water to overflow the incomplete crest, flooding the first turbine hall.

Between 1979 and 1985, the dam’s turbines were gradually brought online from the second to the tenth units. But as water levels rose, signs of structural strain emerged. Seepage, deformations, and cracks in the dam body became increasingly visible.

In 1983–1985, engineers detected a disturbing phenomenon: the rocky foundation beneath the first piers had begun to loosen. Cracks extended up to 36 meters along the concrete interface. Horizontal fractures appeared in the pressure face of the dam between elevation levels 344–386 meters. These defects indicated that the dam was bearing loads it had not been designed to carry a direct consequence of premature loading. In 1985, a severe flood event destroyed the base of the still-incomplete spillway basin. Repairs took more than two years. The ninth and tenth turbines came online during this same period, further increasing the load on the already compromised structure.

Structural vulnerabilities continued to multiply. In 1988, the spillway base was again damaged by water forces. The fourth pier, only completed after the reservoir reached a higher level, never carried its full share of the load, leaving the first pier overstressed. By the late 1980s, tension cracks had propagated from elevations 344 up to 359 meters. The architecture of control had become an architecture of fracture.

By 1996, the situation had become critical. For the first time, authorities made a serious concession: the normal reservoir level was lowered from 540 meters to 539 meters in an attempt to reduce internal stress on the dam body. It was an extraordinary move the equivalent of admitting that the dam’s full capacity was too dangerous to use. But one meter was not enough. Water continued to seep through microcracks and deep fissures, with over 1000 liters per second flowing through the body and base. Between 1996 and 2003, emergency reinforcement was carried out: grouting of the fractured zones, sealing of the pressure face, and partial stabilization of the foundation rock. These measures bought time, but not safety.

2009: Collapse from Within

On the morning of August 17, 2009, at precisely 8:13 a.m., turbine number 2 one of the largest in the facility failed catastrophically. The anchoring bolts that secured its 920-ton lid had sheared off. Years of metal fatigue, exacerbated by dynamic stresses, had weakened the assembly. When it gave way, the turbine was launched into the air like a missile. Water rushed in. The turbine hall flooded within minutes. Seventy-five people were killed. The official investigation revealed a long history of missed inspections, inadequate repairs, and fatigue that had built up unnoticed or ignored. It was the most severe hydropower accident in Russian history.The machine hall was destroyed. Several other turbines were damaged beyond repair. But more than that, the dam’s image, as a monument to control and competence, was irrevocably cracked.

After the disaster of 2009, the Sayano-Shushenskaya dam was rebuilt. Its turbine hall was restored, safety protocols were revised, and modern diagnostic systems were installed. Technically, the facility returned to operation within a few years. But symbolically, the structure was no longer the same.

The rupture affected more than the structure itself, reaching into its symbolic core.

For decades, the dam had represented strength: a concrete testament to the Soviet state’s ability to control nature, to organize territory, to project order across vast space. It had been photographed, idealized, celebrated in diagrams, documentaries, and propaganda. It is infrastructure shaped by ideology and cast into material permanence. This shift was not only symbolic — it exposed how infrastructure, once a confident projection of state capacity, could also reveal the limits of power. The Sayano-Shushenskaya dam became a surface that held not only water and electricity, but the memory of ambition, failure, and control. To understand this dam is to understand how infrastructure itself can become a political form. The Sayano-Shushenskaya dam cannot be understood solely as a technical achievement. It was part of a broader political mechanism, one that treated territory as a system to be ordered, monitored, and extracted from. In this sense, the dam is not just a site of generation, but one of governance.

Throughout the Soviet twentieth century, infrastructure was used to give form to state power. Dams, railways, and pipelines were not just instruments of economic development. They were spatial expressions of control. The building of hydropower stations in remote regions served multiple purposes: they industrialized the periphery, established strategic presence, and realigned the rhythms of everyday life with the calendar of the state.

Energy infrastructure in particular was central to this process. To electrify a region was to integrate it economically and ideologically. The dam, then, was not merely a machine, but a spatial agent. It altered landscapes, determined where people could live, and embedded state intention into physical form.

The Sayano-Shushenskaya project followed this logic. Its location, scale, and form were shaped as much by political calculations as by hydraulic ones. It served as a boundary, a command center, and a visual assertion. It marked where the state had reached, and how far it could project its will.

This dam reveals how infrastructure, beyond its planned function, accumulates meaning across time, as archive, memory and instrument of governance. Built to generate power, it came to embody a system of authority, a geography of intervention and a memory of fracture. Its concrete mass records not only what was planned, but also what exceeded planning, decisions made under pressure, lives displaced, cracks that grew over time. The Sayano-Shushenskaya dam is not alone in this. Across regions and regimes, infrastructure often operates as a medium of political expression. The Soviet project of infrastructural expansion left behind more than technical systems. It produced spatial legacies, where ideology was cast into terrain, and where the consequences of ambition became part of everyday geography.